Joan Mitchell’s Orphans

By Lauren Stroh

September 12, 2025

AbEx giantess Joan Mitchell founded no schools, mothered no children, divorced one husband, and annulled her marriage to another. She lived and worked alone, in privilege, and was committed to her artistry at the expense of the typical life prescribed to a woman of her generation. She was not merely a “nice lady” painting variegated landscapes after Monet’s Giverny… She is likely remembered as an alcoholic, bereft of sentimentality or any semblance of “feminine” warmth. A recollection of the artist at a dinner party appears in a New Yorker review of her 2002 Whitney retrospective. In the article, titled “Tough Love,” Peter Schjeldahl depicts Mitchell as vitriolic, rudely spewing profanities at invited guests and at her lover, the painter Jean-Paul Riopelle, who cowers from the distance of a staircase. This impression lingers, even as this year, the artist would make 100.

Installation view of “History or Premonition.” Photograph by Jeffery Johnston, courtesy of Joan Mitchell Foundation.

A recent show at the Joan Mitchell Center in New Orleans, which this year celebrates a decade of its residency program, closed at the end of last month. The show, organized by two alumni of the program, Josiah Gagosian and Nyeema Morgan, featured the work of forty artists who participated in the residency since its inception. The exhibition’s title, “History or Premonition,” another of those ambiguous, glibly poetic epithets lately popular with curators, was derived from a line of poetry written by Nathan Kernan, taken from his 1992 book Poems, which Mitchell illustrated.

The reference’s application here made for a flimsy curatorial conceit—virtually no interdisciplinary collaboration occurred within the context of this exhibition (or in the residency, for that matter, though this assessment will come to no surprise to those who have been paying attention throughout the years; the program rather regressively limited itself to painters and sculptors then to “visual artists” to the exclusion of other traditionally accepted disciplines [like performance and conceptual art] in its first several cohorts).

A selection of quotes by Mitchell, which appeared as vinyl wall text posted outside the artists’ studios, repurposed into galleries, was offered instead, intended to correspond the work on display with key moments in Mitchell’s life and professional development. Inside, like and unlike works were arranged by theme. Even so, there was little aesthetic congruence between works grouped together. And this textual homage to Mitchell, again slight, proved the only substantiative relationship established between the residency’s namesake artist and those she has supported through her will.

I have asked elsewhere what Mitchell, who moved between Chicago, New York, and France throughout her life, has to do with New Orleans—following research, I can safely conclude: nothing. There is no evidence she visited the city at any point in her life, and her work was only shown here posthumously in a 2010 multivenue symposium hosted at satellite galleries and museums (i.e. the New Orleans Museum of Art, the Contemporary Arts Center, and the Newcomb Art Gallery at Tulane University). This showcase preceded Prospect 1.5 and the Joan Mitchell Foundation’s acquisition of real estate at 2275 Bayou Road in the Seventh Ward, which would become the residency center in 2015. Her work has not returned since.

Which is a pity considering the venue’s pristine beauty and remarkable potential for shows (inside you’ll find studios engineered with abundant natural light and ample space, and the grounds that surround them are a quiet oasis apart from the traffic nearby on Esplanade and Broad). The facilities’ splendour suits Mitchell’s provenance, and they vaguely resemble the minimalist architecture of the Cy Twombly Gallery, a permanent collection of Mitchell’s contemporary’s work, at The Menil Collection in Houston.

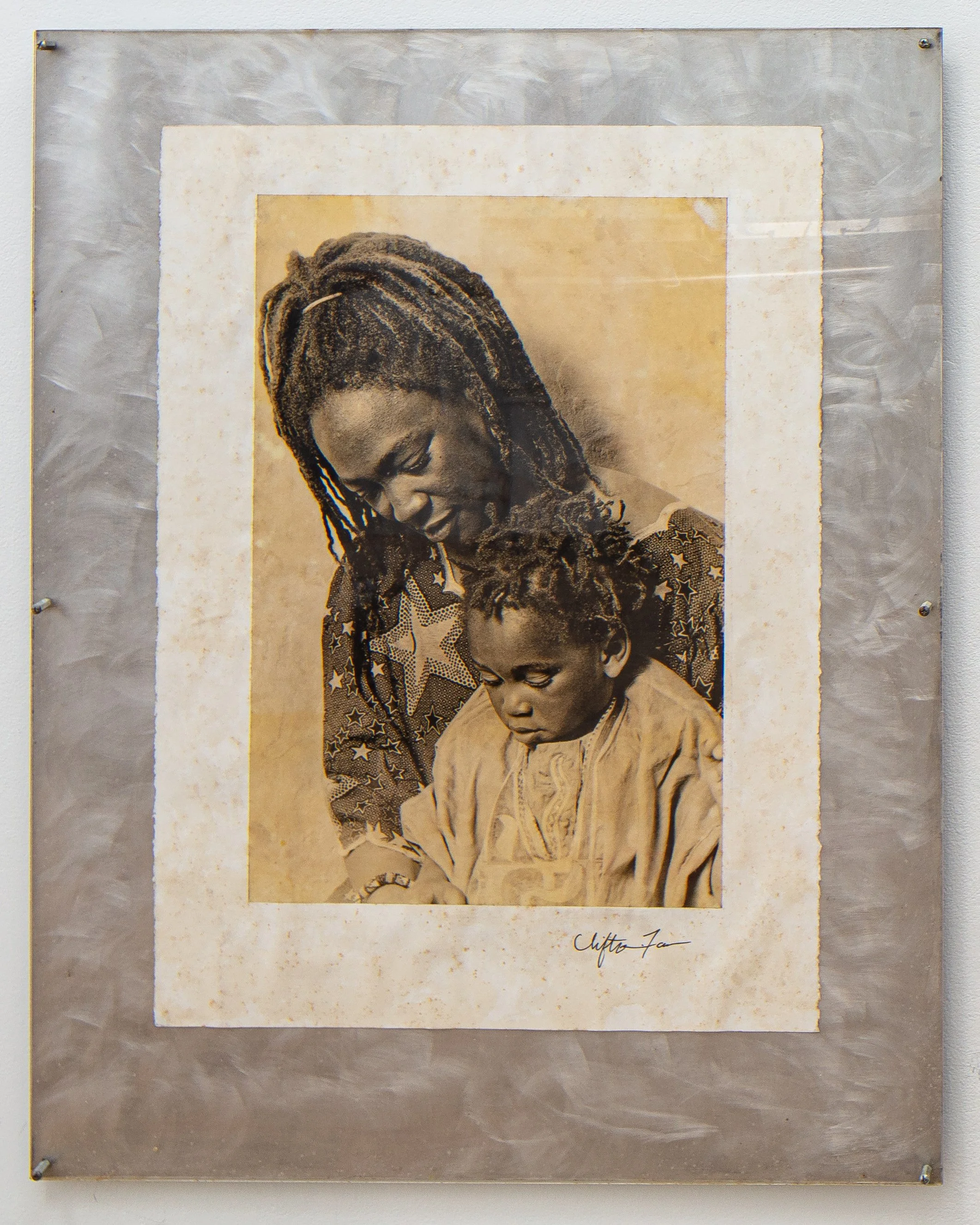

Clifton Faust, My Black Madonna and Child, 1996, Graphic art film positive, coffee stained, linen on brushed aluminum, 31 x 39 inches. Photograph by Jeffery Johnston, courtesy of Joan Mitchell Foundation.

Considering that seventy other venues around the globe have arranged to display Mitchell’s art in this her centennial year, it is disappointing not to see any accommodated in New Orleans, particularly in the context of this exhibition, which ultimately failed to establish a salient relationship between the artist’s oeuvre and that of the residents of the Joan Mitchell Center. This is the first formal exhibition of visual art that has been held in the space, and so its failure might have been irrelevant were it not for an assertion made in the show’s opening remarks by the Center’s Interim Director Veronique Le Melle, who indicated that this exhibition may very well be the space’s last.

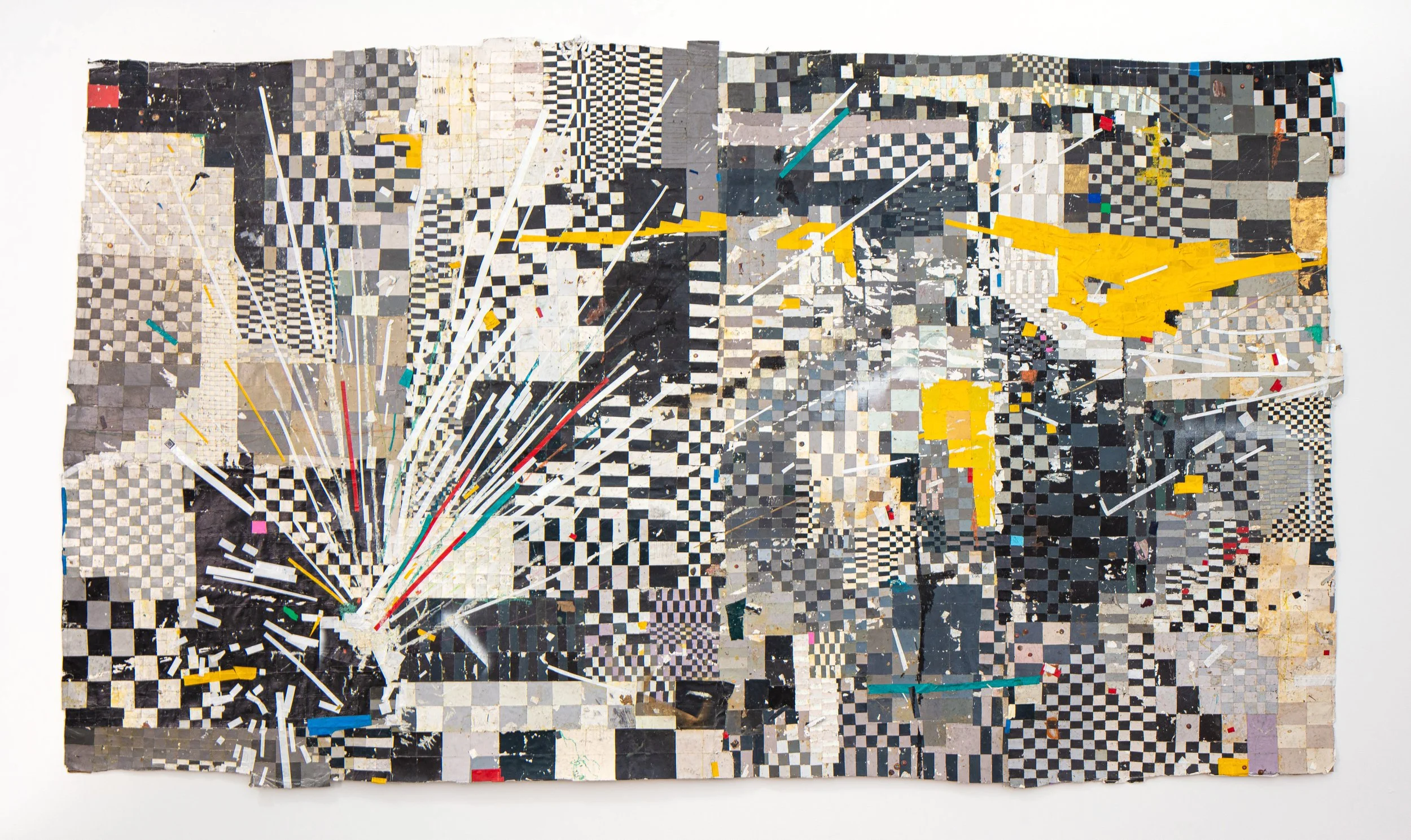

This should not deflect from the talent that has been successfully supported by the program; on display were works of considerable technical competence and integrity, among which I include Clifton Faust’s My Black Madonna and Child (1996) and william cordova’s untitled (rumi maki #101) (2022-2023). But these works were not complimented by an overfull exhibition with limited viewing hours, showcased by and large to the same community who has engaged with the artists previously in open studios also hosted by the Joan Mitchell Center.

Leaving the exhibition, I couldn’t escape the sense that this project—full of the good will and optimistic largesse that is so typical of artistic nonprofits—was an affront to Mitchell’s extraordinary selfishness. Perhaps her works of blithe and beauty (that, yes, earned her considerable commercial success—more than she could exhaust in her lifetime) would overpower the art that the majority of her charity’s beneficiaries display. But I would have appreciated the chance to come to this conclusion myself, and to have done so independent of a context that flattens the legacies of difficult women into that which is palatable and easily dismissed.

william cordova, untitled (rumi maki #101), 2022-2023, Mixed media, 80 x 138 1/2 inches. Photograph by Jeffery Johnston, courtesy of Joan Mitchell Foundation.